In hindsight, perhaps they were hints of things soon to come, connections to the coming conflict between county and Kaiser hidden between the lines of the local news in Genesee County in the winter of late 1916 and early 1917:

[Click on articles for full view in separate tab]

——

“Trail of Fire Left by Meteor Across the Sky”

December 7, 1916 Batavia Daily News

December 7, 1916 Batavia Daily News

“Many people who were out of doors last evening between 7 and 7:30 o’clock had a view of a beautiful celestial visitor that was awe-inspiring in its brilliancy . . . what might have been a golden serpent sinuously working its way through the sky. The head was a ball of fire and the body was a shimmering streak of flame from which the gilded scales fell off as it moved creepingly along.”

“Buffalo Bill’s Remains Will Lie in State in Colorado’s Capital . . . Well Known in Batavia”

January 11, 1916 Batavia Daily News

January 11, 1916 Batavia Daily News

“Many Batavians knew Buffalo Bill well at the time he was a resident of Rochester in 1874 and 1875, as he frequently visited this village during that period. . . . “He was an intimate friend of the late Major Reedy of Batavia, afterward sheriff of Genesee County, who, like Cody, was an old Indian fighter . . . . After the organization of his big Wild West Show Buffalo Bill visited Batavia twice, on July 2, 1892, and the last time on May 28, 1912.”

“Rabid Dogs Are Creating Some Alarm – Many Persons Bitten”

January 13, 1917 Batavia Daily News

January 13, 1917 Batavia Daily News

“The spread of the disease known as rabies has assumed alarming proportions in Western New York,” warned health officials. “Within a week, a boy who was bitten by a strange dog on the streets of Buffalo died of hydrophobia, and some thousands of dollars worth of horses, cattle, sheep, and hogs have died in Western New York from rabies and an even hundred of persons within this same territory have been bitten by dogs, which were found . . . to have had rabies .”

On the other hand, you hardly needed to read between the lines to know that serious trouble was brewing. A mere glance at any day’s headlines would tell you that.

Since August 1914, when the treaty-linked trains of England-France-Russia and Germany-Austria-Hungary had collided head-on and Europe exploded in war, the news in Genesee County from across the sea had been bad at best, and horrifying too often.

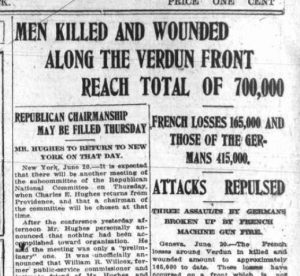

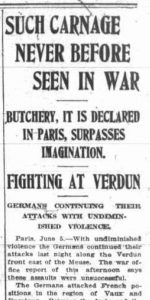

The births of the modern machine gun, torpedo, and tank; of “aeroplanes” that rained bombs; of gas that blinded, burned skin, and flooded lungs; of machinery that coldly flung body-mutilating explosives into distant troops, had spread death and destruction like no war before. By the end of 1916, combined German and Allied casualties totaled more than two million.

In the still-fresh September 1916 presidential election, although Genesee County had voted overwhelmingly for his Republican opponent, Charles Evans Hughes, Woodrow Wilson had won reelection to the Presidency using the slogan, “He Kept Us Out of War.”

Many Americans called for military preparedness in the interests of national defense, and many more raised funds or made bandages for the Red Cross to help the armies overseas. But few wanted the United States to get involved in that unthinkably bloody war thousands of miles away in foreign lands.

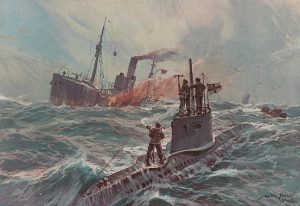

Meanwhile, German submarines nosed along our shores and throughout the Atlantic and Mediterranean prowling for ships carrying, or thought to carry, ammunition and supplies for the Allies. At least, following the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915, in which 128 U.S. citizens had died, and of the Sussex in March 1916, in which several more Americans perished, international outrage had prompted the Germans in May 1916 to limit attacks on commercial ships. Its subs would sink a ship only after a search proved contraband was aboard and only after its crew and passengers had been provided safe passage.

Small comfort, and an agreement that Germany would soon retract, on the final day of January.

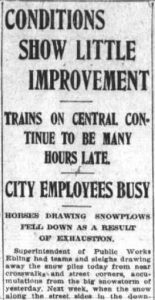

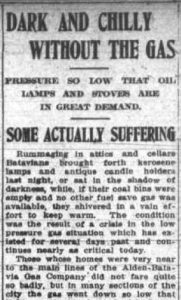

But in those wintry months of December 1916 and January 1917, as blizzard after blizzard swept through western New York, choking roads and stopping trains in their drift-covered tracks, Genesee County residents had worry enough just staying comfortable in their own homes. Coal prices were sky-high, and municipal gas plants could barely keep sufficient pressure up for heating and lighting.

But you have to wonder if anyone noticed, sitting by the fire reading the news as the storms raged outside.

That meteor: Wasn’t Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany’s private yacht named Meteor?

And Buffalo Bill: Wasn’t Kaiser Wilhelm one of Cody’s biggest fans, so admiring the showman’s efficiency in transporting men and animals by train from one performance to another that he had sent members of his Prussian Guard to study his techniques?

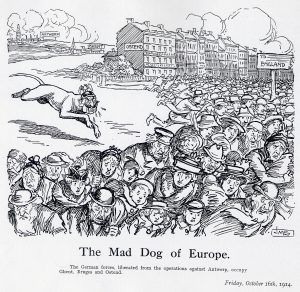

And that scourge of rabid canines spreading across western New York: Wasn’t Kaiser Wilhelm known throughout the world as “The Mad Dog of Europe?”

Next: “Days of Anxious Waiting”

Credits

“Getting on His Nerves?” C.D. Dana (LC-DIG-ppmsca-33521); “Deutsches U-Boot” (LC-DIG-ds-09934); “Kaiser on Ship ‘Meteor'” (LC-DIG-ggbain-04171); “Buffalo Bill” (LC-USZC4-3116): Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

“Mad Dog of Europe” J.M. Stanforth: Courtesy of “Cartooning the First World War” project at Cardiff University.

Newspaper clips: Courtesy of fultonhistory.com.