In Genesee County on New Year’s Day morning, the dawn of 1918, the thermometer plunged to two below. Over the next six weeks, the temperature rarely rose above zero.

But it wasn’t merely the weather that brought a chill to Genesee County that winter.

[Click on articles/documents for full view in separate tab]

The war in Europe was no longer just “over there.” Its impact had come home. The nation was straining to house, clothe, equip, transport and feed an army at home and abroad, while continuing to support its allies with supplies and provide relief to the violence-ravaged people of France and Belgium.

Fuel and food shortages were felt in every American home and business.

January 14, 1918 LeRoy Gazette-News (L) and Batavia Daily News (R)

The fuel situation became so severe that by mid-January the government had ordered all factories east of the Mississippi to close for five days, and to close on every following Monday for six weeks. Hundreds in the county lost work hours.

Retail stores and business offices would have to close, too.

Warming weather allowed the government to lift the mandatory closings in late February, but citizens and businesses were nonetheless strongly urged to voluntarily conserve fuel and food.

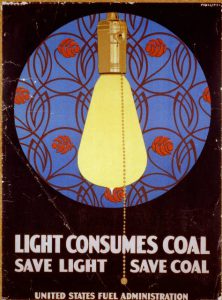

Homeowners were asked to burn wood instead of coal if they had it, and to use as little electricity as possible. Grocers, bakers, and pasta manufacturers were required to use at least 50 percent wheat flour substitutes in their products. Home bakers were told to use the same formula to make “Victory bread” for their families.

“Heatless Mondays, meatless Tuesdays, and wheatless Wednesdays” became a way of life in Genesee County.

Austerity was not only the order of the day, but a patriotic duty.

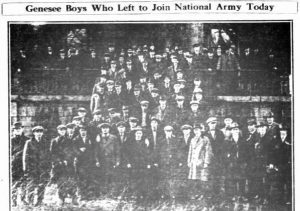

In the meantime, the county was bidding goodbye and good luck to more young men leaving to fight the Kaiser.

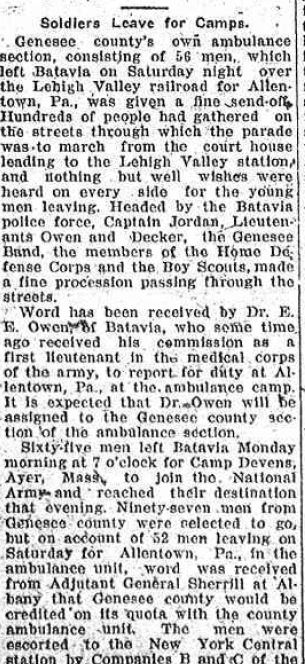

March 2, 1918 Batavia Times

March 2, 1918 Batavia Times

“Hundreds of people had gathered on the streets . . . and nothing but well wishes were heard on every side of the young men leaving.”

On February 23, 56 volunteers left for Camp Crane, in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to serve as Genesee County’s own U.S. Army Ambulance section.

Two days later, 65 more men departed for training at Camp Devens, in Ayer, Massachusetts, as members of the county’s fourth draft contingent.

A fifth Genesee County draft contingent of 42 men would leave on April 4 for Camp Dix, near Wrightstown, New Jersey.

Women, too, were leaving Genesee County, to serve as nurses.

Women, too, were leaving Genesee County, to serve as nurses.

Already, nurses Bessie Boddell of Bergen and Edna Guymer of Pavilion were at Camp Devens, and Anna MacKenzie of Bergen at the base hospital in Camp Beauregard, Louisiana. LeRoy’s Catherine MacPherson, serving at Camp Meade in Maryland, would leave for France in June.

Nora Taft of LeRoy and Florence Carpenter of Batavia had been tending to sick and wounded soldiers at Base Hospital No. 23, near the front in France’s Vosges Mountains, since they’d left in November 1917.

Ruth Randall of LeRoy, who also had sailed for France that November, was caring for soldiers at a hospital near Paris.

Many more women from the county would soon follow.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of newly minted doughboys were shipping out for Europe. News of the arrivals of Genesee County boys in France appeared regularly in local newspapers.

By the end of March, 310,000 American soldiers were in France; by the end of April, there were 430,000; by May’s end, 650,000 had landed on French soil.

The journey across was dangerous. Enemy submarines prowled the waters for troopships; reports of sightings and attacks were common. On February 5, the Tuscania, a converted Scottish luxury liner carrying more than 2,000 U.S. soldiers in a British convoy, was torpedoed and sunk off the coast of Ireland. Over 200 Americans died.

The journey across was dangerous. Enemy submarines prowled the waters for troopships; reports of sightings and attacks were common. On February 5, the Tuscania, a converted Scottish luxury liner carrying more than 2,000 U.S. soldiers in a British convoy, was torpedoed and sunk off the coast of Ireland. Over 200 Americans died.

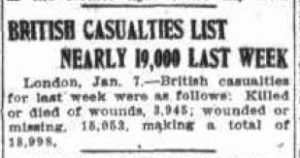

The news from the front, too, was worrisome. All winter long, the war had not been going well for the Allies. Although little ground had been gained on either side, the weekly casualty figures were alarming.

The deadly efficiency of modern weaponry was all too clear.

And the situation would soon get worse.

On the first day of spring, desperate to strike a fatal blow against the British and French before more American troops arrived, Germany launched a series of massive attacks known as the Spring Offensive, or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle), along the Western Front.

March 23, 1918 Batavia Daily News

“A powerful enemy attack delivered with great weight of artillery and infantry has broken the British Defensive system west of St. Quentin.”

On the opening day, March 21, elite German storm troops massed at the Hindenburg Line between Cambrai and St. Quentin and, after an initial five-hour bombardment of more than one million gas and artillery shells, poured through a 19-mile gash in the line.

By the end of the day, 7,500 British soldiers had been killed, 10,000 wounded, and 21,000 captured. Within the next two days, German troops had opened a 50-mile breach in the line and advanced close enough to Paris for its long-range guns to lob shells into the city.

It was into this hellish maelstrom that Genesee County’s young men, and the rest of the doughboys either already on French soil or bound for there, were headed.

It was into this hellish maelstrom that Genesee County’s young men, and the rest of the doughboys either already on French soil or bound for there, were headed.

Although none from the county were yet among them, American soldiers were dying on the battlefield.

That was reason enough for the folks back home to be worried. But there was another reason, too, a lesson already learned five times over in Genesee County:

All soldiers, not only the ones facing fire on the battlefield, and not even just those who were “over there,” were in harm’s way.

The county had already lost five young men in the war to accident and disease.

[Click on highlighted name for full honor roll profile in separate tab]

An accident took the life of Thomas Clark Illes of LeRoy, the first county soldier to die in service after the U.S. entered the war.

An accident took the life of Thomas Clark Illes of LeRoy, the first county soldier to die in service after the U.S. entered the war.

On June 20, 1917, two days before his twenty-second birthday, Illes enlisted at the 74th New York National Guard Armory, the regiment’s headquarters in Buffalo. He was killed on September 8, 1917, a few weeks before the 74th was to leave for training camp in Spartanburg, South Carolina. “The young man had just alighted from an Erie engine on which he had ridden down town from the army camp,” reported the September 10, 1917 Batavia Daily News, “when he was struck at the Kenmore crossing by a Lockport car. He was so badly injured that he died within a few minutes.”

1918’s first war-time death occurred on January 11, when John R Wilder of LeRoy succumbed to pneumonia at an Army hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

1918’s first war-time death occurred on January 11, when John R Wilder of LeRoy succumbed to pneumonia at an Army hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

Wilder, a railroad fireman in civilian life, was a mechanic with the 50th Aero Squadron at Kelly Field, in San Antonio, Texas. “We are considered the finest squadron ever in Kelly Field,” he wrote in a letter to his aunt. “It is quite an honor to belong to such a company of men.” The unit was on its way to Garden City, New York, to depart for overseas duty when John fell ill on January 2 and was sent to the hospital. Wilder, whose wife died in an accident in July 1915, was 27 years old and had two young daughters.

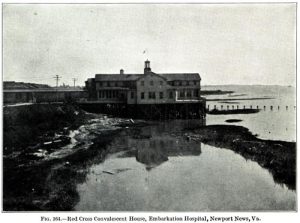

On February 3, 1918, Clifford Barber died of diphtheria in an embarkation hospital in Newport News, Virginia.

On February 3, 1918, Clifford Barber died of diphtheria in an embarkation hospital in Newport News, Virginia.

Clifford, who grew up in Alexander and Bethany, had worked for several years in the composing room of the Batavia Daily News. He enlisted in Rochester on April 28, 1917, just over three weeks after the United States declared war on Germany. In December 1917, his regiment, the 4th Infantry, moved from training at Camp Greene, North Carolina to Newport News to leave for overseas duty. Barber came down with pneumonia while there, and had just recovered from that illness when he contracted diphtheria and died suddenly. He was 20 years old.

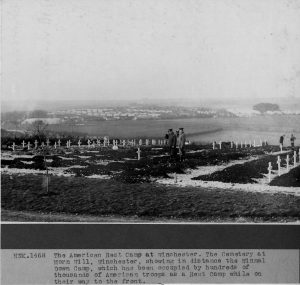

On March 29, 1918, Edgar Murrell became the first Genesee County soldier to lose his life overseas.

On March 29, 1918, Edgar Murrell became the first Genesee County soldier to lose his life overseas.

Murrell, who likely went by his middle name, Roy, was born in Monroe County and spent most of his life there. But around 1915 he moved to LeRoy and was working as a farm hand when he was inducted in September, 1917 and assigned to Battery D of the 307th Field Artillery at Camp Dix. Murrell and a small group of others were transferred out in February 1918 and sent across as replacements. Murrell died of pneumonia and diphtheria before reaching France, at Morn Hill rest camp, a stopping-off place for Europe-bound soldiers near Winchester, England. He was 27 years old.

Willis Curtis Peck enlisted in the Navy in 1915, before America was in the war, and had achieved the rank of Coxswain when he died of tuberculosis on the final day of March 1918 at a naval hospital in Newport, Rhode Island.

Willis Curtis Peck enlisted in the Navy in 1915, before America was in the war, and had achieved the rank of Coxswain when he died of tuberculosis on the final day of March 1918 at a naval hospital in Newport, Rhode Island.

Peck was born in Brockport but grew up in Batavia. He served aboard the USS Rhode Island, a Virginia-class battleship in the Atlantic Fleet, in 1916 and 1917. From May 1917 on, he was based at the U.S. Naval Training Station in Newport, where he suffered from a long illness and was in and out of the hospital until his death at age 25. Willis Peck was Batavia’s first war-time serviceman to be buried at home. All city businesses closed during his funeral.

Credits

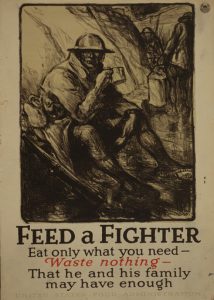

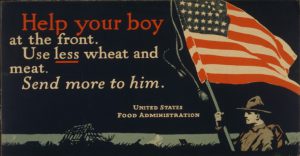

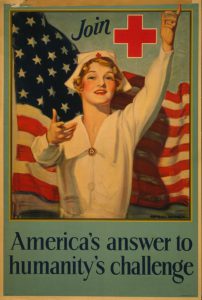

Retrieved from the Library of Congress: “Feed A Fighter,” Morgan Wallace, artist (https://www.loc.gov/item/2002719773/); “Light Consumes Coal,” Coles Phillips, artist (https://www.loc.gov/item/2002712078/); “Be Patriotic – Sign Your County’s Pledge,” Paul Stahr, artist (https://www.loc.gov/item/96515511/); “Help Your Boy at the Front” (https://www.loc.gov/item/2002699354/); “Join [Red Cross] America’s Answer,” Hayden Hayden, artist (https://www.loc.gov/item/2002711989/); Troops on Transport Ship, Official AEF Photo 13912, U.S. Signal Corps (https://www.loc.gov/item/2016826356/); “German Soldiers Marching Toward Albert France” (https://www.loc.gov/item/2005697193/).

Others: “74th Regiment Armory,” author collection; “Aviation Camp, Kelly Field” from Kelly Field Postcards, Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/KellyFieldWWIPostcards); “Embarkation Hospital, Newport News” from Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War Vol. V, Ch.24, Fig. 164 (http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwi/MilitaryHospitalsintheUS/chapter24figure164.jpg); “Scene at an American Rest Camp,” National Archives Photo No. 165-BO-0495 (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/16578345); “USS Rhode Island [19-N-60-4-5]” Naval History and Heritage Command (https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography.html)

Newspaper articles retrieved from fultonhistory.com